Anna Ioannovna: years of reign, history and services to Russia. The reign of Anna Ioannovna (briefly) The reign of Anna Ioannovna became a time of long-awaited

Under Anna Ioannovna, the “timelessness” that followed the death of Peter I continued, that is, the inexpressive, dull period of rule by people who thought only about their own interests and were deeply indifferent to the fate of Russia.

The queen surrounded herself with people devoted and close to her. Ernst Biron was called from Courland, her favorite, with whom she was in love all her life. The time of Anna Ioannovna is called Bironovism.

A smart, educated man, Biron was in the shadows, but held all the threads of control in his hands. At the same time, the interests of Russia were alien to him.

19th century portrait

The leader appointed people loyal to himself in all key positions. They were often Germans from Courland and other foreigners. But a certain number of Biron’s adherents included Russian nobles and nobles. Therefore, one cannot associate Bironovism only with the dominance of the Germans. Biron's supporters were devoted to him, since the government and military posts received from him provided high incomes and the opportunity to use their official position for enrichment (taking bribes, embezzlement of funds).

Biron was matched by other foreigners who came to power together with Anna Ioannovna. The government was headed by A. I. Osterman, and the army was headed by Field Marshal B. Kh. Minich, who were invited to serve in Russia by Peter I.

The Supreme Privy Council was abolished. Instead he appeared Cabinet of Ministers of three people. The Secret Chancellery, liquidated after the death of Peter I, reappeared. The concept of “Bironovism” also includes the creation of an entire system of informers and spies. The Secret Chancellery persecuted people who, at least in words, opposed the empress and her favorite. Both ordinary people and nobles became victims. The organizer of the activities of the Secret Chancellery was one of the associates of Peter I, A. I. Ushakov.

18th century portrait

Having initially been kind to both D.M. Golitsyn and the Dolgorukys (it was impossible to begin the reign with reprisals), Anna Ioannovna, at the insistence of Biron and Osterman, then alienated them. D. M. Golitsyn was subsequently sentenced to death by the court, which was replaced by imprisonment in a fortress, where he died. The Dolgorukys were first sent to their estates, and then almost all of them were sent to Berezov, where Menshikov, exiled due to their machinations, had recently languished. Later, many Dolgorukys were executed after interrogation and cruel torture.

Throughout the reign of Anna Ioannovna, there was a hidden rivalry between Biron and Osterman, between Biron and Minikh. To resist Osterman, Biron achieved the inclusion in the Cabinet of Ministers of Peter I's associate A.P. Volynsky, who at first fervently served his favorite.

However, over time, Volynsky came into power at court and thereby alerted Biron, who teamed up against him with Osterman. They were especially frightened by the fact that Volynsky and his supporters discussed the issue of German dominance. Biron achieved his goal: in 1740, Volynsky and two of his supporters were executed after severe torture.

18th century portrait

Anna Ioannovna held a number of events in the interests of the nobles.

Finally they got what they were waiting for service life limitation. It was installed at 25 years old. This was the first step towards the liberation of the nobles from the heavy “Petrine bondage.” The second step was the abolition of the decree on unified inheritance. From now on, estates could be divided between sons. The third step was the creation Cadet Corps. Noble children emerged from it as officers and no longer pulled the soldier's burden.

- Explain the words “come into power at court.”

Artist J. Delabart

The new government also met the industrialists halfway. They were allowed to buy peasants for their factories without land.

Gradually, Anna Ioannovna paid less and less attention to state affairs. Balls, masquerades, gala lunches and dinners for any occasion followed each other. Meanwhile, the country plunged into the abyss of ruin. The treasury was plundered and depleted.

Coronation: |

|

Predecessor: |

|

Successor: |

|

Birth: |

|

Dynasty: |

Romanovs |

Praskovya Fedorovna |

|

Frederick William (Duke of Courland) |

|

Monogram: |

|

Accession to the throne

Reign of Anna Ioannovna

Domestic policy

Russian Wars

Bironovschina

Appearance and character

End of the reign

A trace in art

Literature

Filmography

Interesting Facts

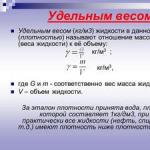

(Anna Ivanovna; January 28 (February 7) 1693 - October 17 (28), 1740) - Russian empress from the Romanov dynasty.

Second daughter of Tsar Ivan V (brother and co-ruler of Tsar Peter I) from Praskovya Fedorovna. She was married in 1710 to the Duke of Courland, Friedrich Wilhelm; Having become a widow 4 months after the wedding, she remained in Courland. After the death of Peter II, she was invited to the Russian throne in 1730 by the Supreme Privy Council as a monarch with limited powers, but took all power by dispersing the Supreme Council.

The time of her reign was later called Bironovism named after her favorite Biron.

Early biography

From 1682, the brothers Peter I and Ivan V reigned on the Russian throne, until the elder but sickly Tsar Ivan V died in 1696. In January 1684, Ivan (or John) married Praskovya Fedorovna Saltykova, who bore the sovereign 5 daughters, of whom only three survived. The eldest daughter Catherine later married Duke Charles Leopold, and her grandson briefly served as Russian Emperor under the name Ivan VI. The middle daughter Anna was born in 1693 and until the age of 15 she lived in the village of Izmailovo near Moscow with her mother Praskovya Fedorovna.

In April 1708, the royal relatives, including Anna Ioannovna, moved to St. Petersburg.

In 1710, Peter I, wanting to strengthen Russia's influence in the Baltic states, married Anna to the young Duke of Courland, Frederick William, nephew of the Prussian king. The wedding took place on October 31 in St. Petersburg, in the palace of Prince Menshikov, and after that the couple spent time at feasts in the northern capital of Russia. Having barely left St. Petersburg at the beginning of 1711 for his possessions, Friedrich Wilhelm died, as they suspected, due to immoderate excesses at feasts.

At the request of Peter I, Anna began to live in Mitau (now the western part of Latvia), under the control of the Russian representative P. M. Bestuzhev-Ryumin. He ruled the duchy, and for a long time was also Anna's lover. Anna gave her consent to marry Moritz of Saxony in 1726, but under the influence of Menshikov, who had plans for the Duchy of Courland, the marriage failed. Around this time, a man entered Anna’s life who retained a huge influence on her until her death.

In 1718, the 28-year-old Courland nobleman Ernest-Johann Buren entered the service in the office of the Dowager Duchess, who later appropriated the French ducal name Birona. He was never Anna's groom, as patriotic writers sometimes claimed, but soon became the manager of one of the estates, and in 1727 he completely replaced Bestuzhev.

There were rumors that Biron's youngest son Karl Ernst (born October 11, 1728) was actually his son from Anna. There is no direct evidence of this, but there is indirect evidence: when Anna Ioannovna went from Mitava to Moscow to become king in January 1730, she took this baby with her, although Biron himself and his family remained in Courland.

Accession to the throne

After the death of Peter II at 1 o'clock in the morning on January 19 (30), 1730, the highest ruling body, the Supreme Privy Council, began to consult about a new sovereign. The future of Russia was determined by 7 people: Chancellor Golovkin, 4 representatives of the Dolgoruky family and two Golitsyns. Vice Chancellor Osterman avoided the discussion.

The question was not easy - there were no direct descendants of the Romanov dynasty in the male line.

Members of the Council discussed the following candidates: Princess Elizabeth (daughter of Peter I), Tsarina-grandmother Lopukhina (1st wife of Peter I), Duke of Holstein (married to Peter I’s daughter Anna), Princess Dolgorukaya (betrothed to Peter II). Catherine I in her will named Elizabeth as heir to the throne in the event of the death of Peter II childless, but this was not remembered. Elizabeth scared off the old nobles with her youth and unpredictability, and the well-born nobility generally did not like the children of Peter I from the former servant and foreigner Ekaterina Alekseevna.

Then, at the suggestion of Prince Golitsyn, they decided to turn to the senior line of Tsar Ivan Alekseevich, who was a nominal co-ruler with Peter I until 1696.

Having rejected the married eldest daughter of Tsar Ivan Alekseevich, Catherine, 8 members of the Council elected his youngest daughter Anna Ioannovna, who had already lived in Courland for 19 years and had no favorites or parties in Russia, to the throne by 8 o’clock in the morning on January 19 (30), which means arranged for everyone. Anna seemed obedient and controllable to the nobles, not prone to despotism. Taking advantage of the situation, the leaders decided to limit autocratic power in their favor, demanding that Anna sign certain conditions, the so-called “ Conditions" According to " Conditions“real power in Russia passed to the Supreme Privy Council, and the role of the monarch was reduced to representative functions.

On January 28 (February 8), 1730, Anna signed “ Conditions“, according to which, without the Supreme Privy Council, she could not declare war or make peace, introduce new taxes and taxes, spend the treasury at her own discretion, promote to ranks higher than colonel, grant estates, deprive a nobleman of life and property without trial, enter into marriage, appoint an heir to the throne.

On February 15 (26), 1730, Anna Ioannovna solemnly entered Moscow, where the troops and senior officials of the state swore allegiance to the empress in the Assumption Cathedral. In the new form of the oath, some previous expressions that meant autocracy were excluded, but there were no expressions that would mean a new form of government, and, most importantly, there was no mention of the rights of the Supreme Privy Council and the conditions confirmed by the Empress. The change was that they swore allegiance to the empress and the fatherland.

The struggle between the two parties regarding the new government system continued. The leaders sought to convince Anna to confirm their new powers. Supporters of autocracy (A. I. Osterman, Feofan Prokopovich, P. I. Yaguzhinsky, A. D. Cantemir) and wide circles of the nobility wanted a revision of the “Conditions” signed in Mitau. The ferment occurred primarily from dissatisfaction with the strengthening of a narrow group of members of the Supreme Privy Council.

On February 25 (March 7), 1730, a large group of nobility (according to various sources from 150 to 800), including many guards officers, came to the palace and submitted a petition to Anna Ioannovna. The petition expressed a request to the empress, together with the nobility, to reconsider a form of government that would be pleasing to all the people. Anna hesitated, but her sister Ekaterina Ioannovna decisively forced the Empress to sign the petition. Representatives of the nobility deliberated briefly and at 4 o'clock in the afternoon submitted a new petition, in which they asked the empress to accept full autocracy and destroy the points of the “Conditions”.

When Anna asked the confused leaders for approval for the new conditions, they only nodded their heads in agreement. As a contemporary notes: “ It was fortunate for them that they did not move then; if they had shown even the slightest disapproval of the nobility's verdict, the guards would have thrown them out the window." In the presence of the nobility, Anna Ioannovna tore " Conditions"and your letter of acceptance.

On March 1 (12), 1730, the people took the oath for the second time to Empress Anna Ioannovna on the terms of complete autocracy.

Reign of Anna Ioannovna

Anna Ioannovna herself was not very interested in state affairs, leaving the management of affairs to her favorite Biron and the main leaders: Chancellor Golovkin, Prince Cherkassky, for foreign affairs Osterman and for military affairs Field Marshal Minich.

Domestic policy

Having come to power, Anna dissolved the Supreme Privy Council, replacing it the next year with a cabinet of ministers, which included A. I. Osterman, G. I. Golovkin, A. M. Cherkassky. During the first year of her reign, Anna tried to carefully attend Cabinet meetings, but then she completely lost interest in business and already in 1732 she was here only twice. Gradually, the Cabinet acquired new functions, including the right to issue laws and decrees, which made it very similar to the Supreme Council.

During Anna's reign, the decree on single inheritance was canceled (1731), the Gentry Cadet Corps was established (1731), and the service of nobles was limited to 25 years. Anna's closest circle consisted of foreigners (E.I. Biron, K.G. Levenwolde, B.X. Minich, P.P. Lassi).

In 1738, the number of Anna Ioannovna’s subjects, residents of the Russian Empire, was almost 11 million people.

Russian Wars

B.X. Minich, who commanded the army, began restructuring the army in a European manner. The Prussian training system was introduced, the soldiers were dressed in German uniforms, ordered to wear curls and braids, and use powder.

According to Minich's designs, fortifications were built in Vyborg and Shlisselburg, and defensive lines were erected along the southern and southeastern borders.

New guards regiments were formed - Izmailovsky and Horse Guards.

Foreign policy in general continued the traditions of Peter I.

In the 1730s, the War of the Polish Succession began. In 1733, King Augustus II died and kinglessness began in the country. France managed to install its protege - Stanislov Leshchinsky. For Russia this could become a serious problem, since France would create a bloc of states along the borders of Russia consisting of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden and the Ottoman Empire. Therefore, when Augustus II's son Augustus III addressed Russia, Austria and Prussia with a "Declaration of the Benevolent" asking for the protection of the Polish "form of government" from French interference, it gave rise to a casus belli (1733-1735).

The French fleet was defeated in Gdansk (Danzig). Leshchinsky fled on a French ship. Augustus III became King of Poland.

Even during the war, French diplomacy, in order to weaken Russia’s efforts in the West, tried to spark a Russian-Turkish conflict. But negotiations with the Turks did not produce the desired results, since the Porte was at war with Iran. However, in 1735, the war with Turkey began due to 20 thousand people traveling to the Caucasus and violating the borders. Tatar troops. Russian diplomacy, aware of the aggressive intentions of the Porte, tried to enlist the friendly support of Iran. For this purpose, the former Iranian possessions along the western and southern shores of the Caspian Sea were transferred to Iran in 1735, concluding the Ganja Treaty. When it became known in Istanbul about the treaty, the Crimean Tatars were sent to Transcaucasia to conquer the lands transferred to Iran.

In the fall of 1735, 40 thousand. General Leontyev's corps, not reaching Perekop, turned back. In 1736, the troops crossed Perekop and occupied the capital of the Khanate, Bakhchisarai, but fearing being surrounded on the peninsula, Minikh, who commanded the troops, hastily left Crimea. In the summer of 1736, the Azov fortress was successfully taken by the Russians. In 1737 they managed to take the Ochakov fortress. In 1736-1738 the Crimean Khanate was defeated.

On the initiative of the Sultan's court, in 1737 a congress on a global settlement of the conflict was held in Nemirov with the participation of the Russians, Austrians and Ottomans. Negotiations did not lead to peace and hostilities resumed.

In 1739, Russian troops defeated the Ottomans near Stavuchany and captured the Khotyn fortress. But in the same year, the Austrians suffered one defeat after another and went to conclude a separate peace with the Porte. In September 1739, a peace treaty was signed between Russia and the Porte. According to the Belgrade Treaty, Russia received Azov without the right to maintain a fleet, a small territory in Right-Bank Ukraine went to Russia; Big and Small Kabarda in the North. The Caucasus and a significant area south of Azov were recognized as a “barrier between two empires.”

In 1731-1732, a protectorate was declared over the Kazakh Junior Zhuz.

Bironovschina

In 1730, the Office of Secret Investigation Cases was established, replacing the Preobrazhensky Order, which was destroyed under Peter II. In a short time it gained extraordinary strength and soon became a kind of symbol of the era. Anna was constantly afraid of conspiracies that threatened her rule, so the abuses of this department were enormous. An ambiguous word or a misunderstood gesture was often enough to end up in a dungeon, or even disappear without a trace; the call “Word and Deed” was revived from “pre-Petrine times.” All those exiled to Siberia under Anna were considered to be over 20 thousand people; for the first time Kamchatka became a place of exile; Of these, more than 5 thousand were those about whom no trace could be found, since they were often exiled without any record in the proper place and with the names of the exiles changed; often the exiles themselves could not say anything about their past, since for a long time, under torture they were inspired by other people's names, for example: “I don’t remember Ivan’s kinship,” without even informing the Secret Chancellery about this. Up to 1,000 people were counted as executed, not including those who died during the investigation and those executed secretly, of which there were many.

The reprisals against nobles: princes Dolgoruky and cabinet minister Volynsky had a particular resonance in society. The former favorite of Peter II, Prince Ivan Dolgoruky, was wheeled on the wheel in November 1739; the other two Dolgorukys had their heads cut off. The head of the family, Prince Alexei Grigorievich Dolgoruky, had previously died in exile in 1734. Volynsky was sentenced to impalement in the summer of 1740 for bad comments about the empress, but then his tongue was cut out and his head was simply chopped off.

Patriotic representatives of Russian society in the 19th century began to associate all abuses of power under Anna Ioannovna with the so-called dominance of the Germans at the Russian court, calling Bironovism. Archival materials and research by historians do not confirm the role of Biron in the theft of the treasury, executions and repressions, which was later attributed to him by writers in the 19th century.

Appearance and character

Judging by the surviving correspondence, Anna Ioannovna was a classic type of landowner lady. She loved to be aware of all the gossip, the personal lives of her subjects, and gathered around her many jesters and talkers who amused her. In a letter to one person she writes: “ You know our character, that we favor people who would be forty years old and as talkative as that Novokshchenova" The Empress was superstitious, amused herself by shooting birds, and loved bright outfits. State policy was determined by a narrow group of trusted persons, among whom there was a fierce struggle for the favor of the empress.

Anna Ioannovna's reign was marked by huge expenses for entertainment events, expenses for holding balls and maintaining the courtyard, tens of times higher than the expenses for maintaining the army and navy; under her, for the first time, an ice town appeared with elephants at the entrance from whose trunks burning oil flowed like a fountain, later during the the clownish wedding of her court dwarf, the newlyweds spent their wedding night in an ice house.

Lady Jane Rondeau, wife of the English envoy to the Russian court, described Anna Ioannovna in 1733:

|

She is almost my height, but somewhat thicker, with a slender figure, a dark, cheerful and pleasant face, black hair and blue eyes. His body movements show some kind of solemnity that will amaze you at first glance; but when she speaks, a smile plays on her lips, which is extremely pleasant. She talks a lot to everyone and with such affection that it seems as if you are talking to someone equal. However, she does not lose the dignity of a monarch for a single minute; It seems that she is very merciful and I think that she would be called a pleasant and subtle woman if she were a private person. The Empress's sister, the Duchess of Mecklenburg, has a gentle expression, good physique, black hair and eyes, but is short, fat and cannot be called a beauty; She has a cheerful disposition and is gifted with a satirical look. Both sisters speak only Russian and can understand German. |

The Spanish diplomat Duke de Liria is very delicate in his description of the Empress:

The Duke was a good diplomat - he knew that in Russia letters from foreign envoys are opened and read.

There is also a legend that, in addition to Biron, she had a lover - Karl Wegele

End of the reign

In 1732, Anna Ioannovna announced that the throne would be inherited by a male-line descendant of her niece Elizabeth-Ekaterina-Christina, daughter of Ekaterina Ioannovna, Duchess of Mecklenburg. Catherine, Anna Ioannovna’s sister, was given by Peter I in marriage to the Duke of Mecklenburg Karl-Leopold, but in 1719 with her one-year-old daughter she left her husband for Russia. Anna Ioannovna looked after her niece, who after baptism into Orthodoxy received the name Anna Leopoldovna, as if she were her own daughter, especially after the death of Ekaterina Ioannovna in 1733.

In July 1739, Anna Leopoldovna was married to the Duke of Brunswick Anton-Ulrich, and in August 1740 the couple had a son, John Antonovich.

On October 5 (16), 1740, Anna Ioannovna sat down to dine with Biron. Suddenly she felt sick and fell unconscious. The disease was considered dangerous. Meetings began among senior dignitaries. The issue of succession to the throne was resolved long ago; the empress named her two-month-old child, Ivan Antonovich, as her successor. It remained to be decided who would be regent until he came of age, and Biron was able to gather votes in his favor.

On October 16 (27), the sick empress had a seizure, foreshadowing her imminent death. Anna Ioannovna ordered Osterman and Biron to be called. In their presence, she signed both papers - on the inheritance after her of Ivan Antonovich and on the regency of Biron.

At 9 o'clock in the evening on October 17 (28), 1740, Anna Ioannovna died at the 48th year of her life. Doctors declared the cause of death to be gout combined with stone disease. During the autopsy, a stone the size of a little finger was found in the kidneys, which was the main cause of death. She was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

A trace in art

Literature

- V. Pikul “Word and Deed”

- Anna Ioannovna is one of the main characters in Valentin Pikul’s novel “Word and Deed.”

- M. N. Volkonsky “Prince Nikita Fedorovich”

- I. I. Lazhechnikov. "Ice House"

- Coronation album of Anna Ioanovna

Filmography

- 1983 - Demidovs. Episode 2. - Lidiya Fedoseeva-Shukshina

- 2001 - Secrets of palace coups. Russia, XVIII century. Film 2. The Empress's Will. - Nina Ruslanova

- 2001 - Secrets of palace coups. Russia, XVIII century. Film 5. The Emperor's Second Bride. - Nina Ruslanova

- 2003 - Secrets of palace coups. Russia, XVIII century. Film 6. Death of the Young Emperor. - Nina Ruslanova

- 2003 - Russian Empire. Series 3. Anna Ioannovna, Elizaveta Petrovna.

- 2008 - Secrets of palace coups. Russia, XVIII century. Film 7. Vivat, Anna! - Inna Churikova

- There is a legend according to which, shortly before her death, the empress was seen talking with a woman very similar to Anna Ioannovna herself. The Empress later stated that it was her death.

For Russian weapons, 1709 was full of glorious victories. Near Poltava, Peter the Great defeated the army - Russian troops successfully drove them out of the Baltic territory. In order to strengthen his influence in the conquered lands, he decided to marry one of his many relatives to the Duke of Courland, Friedrich Wilhelm.

The Emperor turned to his brother’s widow, Praskovya Fedorovna, for advice: which of her daughters did she want to marry off to the prince? And since she really didn’t like the foreign groom, she chose her unloved seventeen-year-old daughter Anna. This was the future Empress Anna Ioannovna.

Childhood and adolescence of the future empress

Anna was born on January 28, 1693 in Moscow, in the family of Peter the Great's older brother. She spent her childhood in Izmailovo with her mother and her sisters. As contemporaries noted, Anna Ioannovna was a withdrawn, silent and uncommunicative child. From an early age she was taught literacy, German and French. She learned to read and write, but the princess never mastered dancing and social manners.

Anna's wedding was celebrated on October 31, 1710 in the unfinished St. Petersburg Menshikov Palace. At the beginning of the next year, Anna Ioannovna and the Duke of Courland left for the capital Mitava. But on the way, Wilhelm unexpectedly died. So the princess became a widow a couple of months after the wedding.

Years before Anna's reign

Peter the Great ordered Anna to remain as ruler in Courland. Realizing that his not very smart relative would not be able to serve the interests of Russia in this duchy, he sent Pyotr Bestuzhev-Ryumin with her. In 1726, when Bestuzhev-Ryumin was recalled from Courland, Ernst Johann Biron, a nobleman who had dropped out of Königsberg University, appeared at Anna’s court.

After the death of Peter the Great, a completely unheard-of thing happened in the Russian Empire - a woman ascended the throne! Widow of Peter I, Empress Catherine. She ruled for almost two years. Shortly before her death, the Privy Council decided to choose Peter the Great's grandson, Peter Alekseevich, as emperor. He ascended the throne at the age of eleven, but died of smallpox at fourteen.

Conditions, or Execution of Secret Society Members

The Supreme Privy Council decided to call Anna to the throne, while limiting her autocratic power. They drew up the “Conditions”, which formulated the conditions under which Anna Ioannovna was invited to take the throne. In accordance with this paper, without the permission of the Privy Council, she could not declare war on anyone, enter into peace agreements, command an army or guard, raise or introduce taxes, and so on.

On January 25, 1730, representatives of the secret society brought the “Conditions” to Metawa, and the duchess, agreeing to all the restrictions, signed them. Soon the new Empress Anna Ioannovna arrived in Moscow. There, representatives of the capital's nobility submitted a petition to her asking her not to accept the rules, but to rule autocratically. And the empress listened to them. She publicly tore up the document and dispersed the Supreme Privy Council. Its members were exiled and executed, and Anna was crowned in the Assumption Cathedral.

Anna Ioannovna: years of reign and the influence of her favorite favorite on politics

During the reign of Anna Ioannovna, a cabinet of ministers was created, in which one of the vice-chancellors, Andrei Osterman, played the main role. The empress's favorite did not interfere in politics. Although Anna Ioannovna reigned alone, the years of her reign are known in Russian historiography as the Bironovschina.

In January 1732, the imperial court moved to St. Petersburg. Here Anna, who had lived in Europe for a long time, felt more comfortable than in Moscow. Foreign policy during the reign of Anna Ioannovna was a continuation of the policy of Peter the Great: Russia was fighting for the Polish inheritance and entered into a war with Turkey, during which Russian troops lost one hundred thousand people.

Merits of the Empress to the Russian State

What else did Anna Ioannovna do for Russia? The years of her reign were marked by the development of new territories. The state conquered the steppe between the Bug and the Dniester, but without the right to keep ships on the Black Sea. The great Northern Expedition begins to work, Siberia and the coast of the Arctic Ocean and Kamchatka are explored.

By decree of the Empress, one of the most ambitious construction projects in the history of the Russian Empire begins - the construction of a colossal system of fortifications along the southern and southeastern borders of European Russia. This large-scale construction, which began during the reign of Anna Ioannovna, can be called the first cultural and social project of the Russian Empire in the Volga region. The Orenburg expedition operates on the eastern borders of the European part of the empire, for which the government of Anna Ioannovna set numerous tasks.

Illness and death of the empress

While guns thundered on the borders of the empire and soldiers and nobles died for the glory of the empress, the capital lived in luxury and entertainment. Anna's weakness was hunting. In the rooms of the Peterhof Palace there were always loaded guns, from which the Empress fired at flying birds. She loved to surround herself with court jesters.

But Anna Ioannovna knew how to not only shoot and have fun; her years of reign were associated with very serious state affairs. The empress ruled for ten years, and all these years Russia built, fought and expanded its borders. On October 5, 1740, at dinner, the empress lost consciousness and, after being ill for twelve days, died.

The analysis of sources for the period 1730-1740, carried out in the work, allows us to highlight the reasons for the emergence of a stable negative assessment of Anna’s reign. The main reason is the stereotype of “Bironovism,” which began to take shape during the Elizabethan reign, and was then consolidated in popular literature of the first half of the 19th century. Having penetrated widely into the mass historical consciousness, it could not help but be reflected in the works of domestic historians. Other reasons include the state of public consciousness in Russia in the second half of the 19th century and during Soviet times.

As for the modern assessment of the period of the 1730s, the prevailing belief is that Anna’s reign became a time of long-awaited stability, after a series of “palace coups” and Peter’s upheavals. A number of serious measures were taken in the social sphere, in the field of regulation of industry and trade, management, etc. Anna’s government chose a fairly clear political course aimed at strengthening the reforms carried out by Peter the Great and preserving Russia’s foreign policy positions.

Should be excluded from the characteristics of the period of the 1730s. the term "German dominance". After comparing two points of view on the role of the German factor in Russian politics, it becomes clear that this definition of the activities of many talented foreigners in the service of the Russian Empire is unfair. Among them were not only statesmen, but also people of science and art, who left their unique mark on the history of Russian culture. We should also not forget that it was during this “dark era” that the cadet corps was opened and the first opera was staged. This can be attributed to the trends of the time, however, the fact that Anna’s government took these trends into account is no small merit; this indicates a desire for development based on the experience of the more developed countries of Europe. Of course, against the backdrop of such striking phenomena of Russian history as the reforms of Peter the Great and the “enlightened absolutism” of Catherine II, the ten-year reign of Anna Ioannovna looks more than inexpressive, for this reason there are still all those cliches that were easy to create, but so difficult to destroy everything still exist in Russian historiography. Is it possible to compare such rulers as Anna and Catherine? Such statesmen as Menshikov and Biron? This is probably the historian’s task, to see something significant where at first glance it is not there. If we compare traditional and modern assessments of the reign of Anna 1, it is easy to notice the advantages of the latter. Logical and well-founded conclusions in it are based on a much wider range of sources on the problem, in contrast to the traditional position, the conclusions of which were often drawn only from indirect sources.

The question of Anna’s reign remains open, because it is still very poorly studied, not enough attention is paid to the personalities of the leading statesmen of that era at the head of public administration, such as Minikh, Osterman, Cherkassky, Volynsky, etc. a number of issues related to both domestic and foreign policy are not covered. Historians do not use an entirely sufficient number of sources on the problem.

There are already some hints at a rethinking of Anna Ioannovna’s political activities, in particular in the studies of Kurukin and Kamensky. Even earlier, Karnovich subjected the image of Anna Ioannovna to revision. But the percentage of such works is still too small to make any generalizations.

After conducting research on the problem, we come to the conclusion that despite the fact that Anna Ioannovna was a mediocre ruler and poorly versed in politics, thanks to the successfully created government, which included such talented and knowledgeable people as Minikh, Osterman and others, Russia throughout the decade of her reign developed and strengthened in conditions of internal political stability.

D/f "Russian Tsars: the reign of Anna Ioannovna (1730–1740)" | Buffoonery at court and interesting facts.

So, in 1730, unexpectedly for everyone (and for herself), Anna Ivanovna became autocrat. Contemporaries left mostly unfavorable reviews about her. Ugly, overweight, loud, with a heavy and unpleasant look, this 37-year-old woman was suspicious, petty and rude. She lived a difficult life.

Anna was born in 1693 into the royal family and in 1696, after the death of her father, Tsar Ivan V Alekseevich, she settled with her mother, Dowager Tsarina Praskovya Fedorovna and sisters Ekaterina and Praskovya in the Izmailovo Palace near Moscow. This is where she spent her childhood. In 1708 it suddenly ended. By decree of Peter I, the family of Tsarina Praskovya Fedorovna moved to live in St. Petersburg. Soon, in 1710, Anna was married to Friedrich Wilhelm, the Duke of the neighboring state of Courland (in the territory of modern Latvia). So Peter wanted to strengthen Russia’s position in the Baltic states and become related to one of the famous dynasties of Europe. But the newlyweds lived together for only 2 months - at the beginning of 1711, on the way to Courland, the Duke unexpectedly died.

Portrait of Tsar Ivan V, Moscow Kremlin Museums

Nevertheless, Peter I ordered Anna to go to Mitava and settle there as the widow of the duke. Both in the case of marriage and in the story of moving to a foreign country, no one asked Anna. Her life, like the life of all other subjects of Peter the Great, was subordinated to one goal - the interests of the state. Yesterday's Moscow princess, who became a duchess, was unhappy: poor, dependent on the will of the tsar, surrounded by a hostile Courland nobility. Coming to Russia, she also did not find peace. Queen Praskovya did not love her middle daughter and until her death in 1723, she tyrannized her in every possible way.

Tsarina Praskovya Fedorovna Saltikova, widow of Ivan V

Changes in Anna's life date back to 1727, when she found a favorite, Ernst-Johann Biron, to whom she became strongly attached and began entrusting him with state affairs. It is known that Anna did not understand the government of the country. She did not have the necessary preparation for this - she was taught poorly, and nature did not reward her with intelligence. Anna had no desire to engage in government affairs. With her behavior and morals, she resembled an uneducated small landowner who looks out the window with boredom, sorts out the squabbles of the servants, marries her associates, and laughs at the antics of her jesters. The antics of jesters, among whom there were many noble nobles, formed an important part of the life of the empress, who also loved to keep around her various wretched, sick, midgets, fortune tellers and freaks. Such a pastime was not particularly original - this is how her mother, grandmother and other relatives lived in the Kremlin, who were always surrounded by hangers-on who scratched their heels at night, and fairy-tales.

Portrait of the Duke of Courland E. I. Biron

Russian tsars: Anna Ioannovna Years of reign: 1730 - 1740 (WATCH VIDEO)

Empress Anna Ioannovna. 1730s.

Portrait of Anna Ioannovna on silk. 1732 g

Anna was a person of a turning point, when the old in culture was replaced by the new, but coexisted with it for a long time. Therefore, along with the traditional jesters and hangers-on at Anna’s court, Italian operas and comedies were staged in a specially built theater with a thousand seats. During dinners and holidays, opera singers and ballerinas delighted the hearing and sight of the courtiers. Anna's time entered the history of Russian art with the founding of the first ballet school in 1737. A choir was formed at the court, and the composer Francesco Araya, invited from Italy, worked. But most of all, Anna, unlike the Moscow princesses, was fond of hunting, or rather shooting. It was not just a hobby, but a deep passion that gave the queen no rest. She often shot at crows and ducks flying in the sky, and hit targets in the indoor arena and in the parks of Peterhof.

She also took part in grandiose hunts, when the beaters, having covered a gigantic expanse of the forest, gradually (often over weeks) narrowed it and drove the forest inhabitants into the clearing. In the middle of it stood a special tall carriage - a Jagt-Wagen - with the armed empress and her guests. And when the animals, mad with horror: hares, foxes, deer, wolves, bears, moose, ran out into the clearing, prudently fenced with a wall made of ship's canvas, then a disgusting massacre began. In the summer of 1738 alone, Anna personally shot 1,024 animals, including 374 hares and 608 ducks. It’s hard to even imagine how many animals the queen killed in 10 years!

Buffoonery at the court of Anna Ioannovna

Valery Jacobi (1834-1902) Jesters at the court of Empress Anna

(The composition includes 26 figures: jesters playing leapfrog are trying to cheer up those gathered in the bedroom of the ailing Empress Biron (sitting at her head) and the courtiers. These are M.A. Golitsyn (standing bent over) and N.F. Volkonsky (jumped on him), A.M. Apraksin (stretched out on the floor), the jester Balakirev (towers above everyone), Pedrillo (with a violin) and D'Acosta (with a whip). Countess Biron is at the bed, state lady N.F. is playing cards at the table Lopukhina, her favorite Count Levenwolde and the Duchess of Hesse-Homburg, behind them are Count Minikh and Prince N. Trubetskoy. Next to Biron is his son with a biochm and the head of the Secret Chancellery A.I. Ushakov. The future ruler Anna Leopoldovna is sitting nearby. Ambassador de Chatardy and physician Lestok. On the floor, near the bed, is the Kalmyk dwarf Buzheninova. To the side, at the perch with parrots, is the poet V.K. Trediakovsky, looking indignantly at the entrance.

More is known about Anna Ioannovna's jesters than about her ministers. The jester Ivan Balakirev is especially famous.

In 1735, the Empress wrote to Moscow Governor-General Saltykov:

Semyon Andreevich! Prince Nikita Volkonsky sent someone to the village on purpose... and led them to ask people... how he lived and who his neighbors knew, and how he received them - arrogantly or simply, also what he did for fun, whether he rode with dogs or what other pastime he had... and when at home, how he lived, and whether his mansion was clean, whether he ate stumps and lay on the stove... How many shirts did he have and how many days did he sew on a shirt?

This letter is about the new court jester Prince Volkonsky. The search for the most worthy candidates for court fools was a responsible matter. That’s why Anna wanted to know what Prince Volkonsky’s personality was like, whether he was clean, whether he spoiled the air in the wards, and what he enjoyed in his free time.

Not every candidate could become one of the court fools and “fools” (that’s what firecrackers were called. - E. A.). Less than a few years later, among the jesters of Anna Ioannovna’s court were the best, “selected” fools in Russia, sometimes famous and titled people. I would like to note right away that the title of prince or count did not open the way to becoming a jester. At the same time, neither the jesters themselves, nor those around them, nor Anna Ioannovna perceived appointments as jesters as an insult to noble honor. It was clear to everyone that the jester, the fool, was fulfilling his “duty,” mindful of its clear boundaries. The rules of this position-game included both well-known responsibilities and well-known rights. The jester, indeed, could say something impartial, but he could also suffer if he went beyond the limits set by the ruler. And yet the role of the jester was very significant, and they were afraid to offend the jester...

Anna's "staff" included six jesters and about a dozen Lilliputians - "Carls".

Wedding of dwarfs in 1710.

The most experienced was the “Samoyed king” Jan d’Acosta, to whom Tsar Peter I once gave a deserted sandy island in the Gulf of Finland. Peter often talked with the jester on theological issues - after all, the memorable cosmopolitan, Portuguese Jew d'Acosta could compete in knowledge of the Holy Scriptures with the entire Synod. The above-mentioned Volkonsky, a widower, the husband of that poor Asechka, whose salon was destroyed by Menshikov, also became a full-fledged jester at Anna’s court.

He had important responsibilities - he fed the Empress's favorite dog Tsitrinka and acted out an endless buffoon performance - as if he had mistakenly married Prince Golitsyn. With another jester, the Neapolitan Pietro Miro (or in the Russian, more obscene version of “Pedrillo”) Anna usually played the fool, he also held the bank in a card game. He also carried out various special assignments for the Empress: he traveled to Italy twice and hired singers there for the Empress, bought fabrics, jewelry, and he himself dealt in velvet. Count Alexei Petrovich Apraksin was from a noble, royal family, the nephew of Admiral General F. M. Apraksin and Tsarina Marfa Matveevna. This jester was a prankster by vocation. Nikita Panin said about him that “he was an obnoxious buffoon, he always offended others and was often beaten for it.” Perhaps he received rich awards from the empress for the zealous performance of his duties.

The life and fate of another noble jester - Prince Mikhail Golitsyn - is very tragic. He was the grandson of Prince Vasily Vasilyevich Golitsyn, the first dignitary of Princess Sophia, lived with his grandfather in exile, then was enlisted as a soldier. In 1729 he went abroad. In Italy, Golitsyn converted to Catholicism, married an Italian commoner, and then returned to Russia with her and the child born in this marriage. Golitsyn carefully hid his new faith and marriage to a foreigner. But then everything was revealed, and as punishment for his apostasy, Golitsyn was made a jester. Everything could have happened differently, and Golitsyn would have ended up, at best, in a monastery.

However, information about Golitsyn's extraordinary stupidity reached Empress Anna. She ordered him to be brought to St. Petersburg and taken to court. Traces of his unfortunate Italian wife are lost in the Secret Chancellery. Her husband lived happily at court and received the nickname Kvasnik, because he was assigned to bring kvass to the empress. It was this Kvasnik that Anna Ioannovna decided to clownishly marry in the famous Ice House, built in the spring of 1740 on the Neva...

Ivan Ivanovich Lazhechnikov "Ice House" Historical novel (read online)

Ice House - Valery Ivanovich JACOBI (1833-1902)

Characters: Jester Ivan Balakirev

But still, Ivan Emelyanovich Balakirev was unanimously recognized as the main jester of Empress Anna. A stalwart nobleman, dexterous and intelligent, he somehow attracted the attention of the court and was enrolled in the court staff. Balakirev suffered greatly at the end of the reign of Peter I, being drawn into the affair of Queen Catherine's favorite Willim Mons. He allegedly worked as a “postman” for his lovers, carrying notes, which is quite possible for a voluntary jester. For his connection with Mons, Balakirev received 60 blows with sticks and was sent to hard labor. Such circumstances, as we know, do little to promote a humorous view of the world. Fortunately for Balakirev, Peter soon died, Catherine I rescued a faithful servant from hard labor, and under Anna Ioannovna, the retired warrant officer Balakirev became a jester. It was then that he became known as a great wit and a wonderful actor.

Any professional buffoonery is always a performance, a performance. Anna and her entourage were big hunters of jester performances, “plays” of jesters. Of course, behind this was the ancient perception of buffoonery as a stupid, traditional life turned inside out, the clownish reproduction of which made the audience laugh until it made them laugh, but was sometimes incomprehensible to a foreigner, a person of a different culture. Each jester had his own, established role in the “play.” But Balakirev’s interlude jokes, heavily mixed with obscenity, were especially funny; they sometimes dragged on for years. At court, Balakirev’s card “play” was played out for a long time - he began to lose a horse in a court card game. Anna wrote to Moscow that Balakirev had already lost half of the horse and asked senior officials to help the unfortunate man win back the animal. Not only court and high officials, but also church hierarchs were drawn into Balakirev’s buffoonish “performances.” Once Balakirev began to publicly complain about his wife, who refused him bed. This “incident” became the subject of long buffoonish proceedings, and then the Synod at its meeting decided to “enter into marital intercourse as before” for Balakirev with his wife. The piquancy of the whole situation was given by the well-known fact of Biron’s cohabitation with Anna. Almost as openly as Balakirev’s troubles were discussed at court, in society they said that Biron and Anna were living somehow very boringly, “in a German, bureaucratic way,” and this caused ridicule.

The laughter caused by the antics of one jester always upset others. From time to time, obscene feuds and fights between the jesters broke out, and the whole courtyard rolled with laughter, remembering the “battles” of this “war”... Meanwhile, the fights between the jesters were serious. The struggle for the empress's favor here was no less intense than among courtiers and officials: with slander, meanness, and even massacres. And this was funny... The quarrels and fights of the jesters especially amused the empress. But you should know that making people laugh is a dirty job and a rather disgusting sight. If we had a chance to see the jokes of Balakirev and others like him, then we would not have experienced anything other than disgust for this obscene performance, mixed with vulgar jokes about manifestations of the “lower classes”. People of the past had a different attitude towards obscene words and rude antics of jesters. The psychological nature of buffoonery was that the jester, speaking obscenities, exposing his soul and body, gave an outlet to the psychic energy of the audience, which was kept under wraps by the strict, sanctimonious norms of the morality of that time. As historian Ivan Zabelin writes, “that’s why there was a fool in the house, to personify the stupid, but in essence, free movements of life.” Empress Anna was a prude, a guardian of public morality, but at the same time she was in an illegal relationship with the married Biron. These relations were condemned by faith, law and people. The Empress knew this very well from reports from the Secret Chancellery. Therefore, it is possible that the jesters, with their obscenity and obscenity, exposing the “bottom”, allowed the empress to relieve unconscious tension and relax. Only Balakirev himself was not funny. This was his job, his service, hard and sometimes dangerous. Therefore, when Empress Anna died in 1740, Balakirev begged to go to his Ryazan village and spent the rest of his life there, in peace and quiet, 20 years. Balakirev has already made his joke.

A notable event of the Annen era was the construction of the Ice Palace on the ice of the Neva in February 1740. This was done for the clownish wedding of Prince Mikhail Golitsyn, nicknamed Kvasnik, with Kalmyk Avdotya Buzheninova.

Near the palace there were ice bushes with ice branches on which ice birds sat. The life-size ice elephant trumpeted as if alive and threw burning oil out of its trunk at night. The house itself was even more shocking: through the windows, glazed with the thinnest pieces of ice, one could see furniture, dishes, objects lying on the tables, even playing cards. And all this was made of ice, painted in natural colors for each item! There was a “cozy” ice bed in the ice bedroom.

After long ceremonies, more like bullying, the newlyweds were brought into the bedroom in a cage, like animals. Here they spent the whole night under the guard of soldiers, so that the cold did not touch a tooth. But the queen and her courtiers were very pleased with the ice festival.

Legends and rumors: Tsar Bell

Under Anna, in 1735, the famous Tsar Bell was cast for the bell tower of Ivan the Great in the Kremlin, as it was called in documents - the “Uspensky Great Bell”. This work was entrusted to the foundry worker Ivan Matorin. The previous bell, cast in 1654, fell and broke during a fire in 1701 under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. Its enormous fragments (it weighed 8 thousand pounds), lying at the foot of the bell tower ever since, attracted everyone's attention. In 1731, Empress Anna decided to cast a new, even larger bell weighing 9 thousand pounds in memory of her royal grandfather. Drawings were made; the “images and persons” of Anna Ioannovna and Alexei Mikhailovich were to be depicted on the surface of the bell. In the autumn of 1734, casting, or rather, kindling, of copper began in special blast furnaces. The furnaces burned continuously for two days, but suddenly on the third day part of the copper broke through and went under the furnace. Matorin, in order to make up for the loss, began throwing old bells, tin, and old copper money into the furnace. However, the melted copper again burst out of the furnaces, and the structures surrounding the furnace caught fire. The fire was extinguished with difficulty, and the casting of the bell ended in complete failure. Soon Matorin died from grief, and his work was continued by his son Mikhail, who was his father’s assistant. On November 25, 1735, the bell was cast. We don’t know when the bell received the now familiar name “Tsar Bell,” but there is no other copper monster like it anywhere in the world. It weighs even more than Empress Anna wanted - 12,327 pounds. After casting, the bell remained standing in a deep hole, because there was no way to lift it. Only a hundred years later, in 1836, and only the second time, this giant was pulled out of the pit in 42 minutes and 33 seconds by the great engineer and architect Auguste Montferrand, the creator of the Alexander Pillar and St. Isaac's Cathedral. Perhaps the bell would have been raised earlier, but there was no urgent need for this - no one needed it a long time ago. The fact is that a year after the bell was cast, on May 29, 1737, a terrible fire started in the Kremlin. It engulfed the wooden structure above the pit in which the bell stood. Firefighters extinguished the fire by dousing it with water. By this time the bell was hot, and as soon as the water hit it, it burst. The largest bell in the world never sounded...

On October 5 (16), 1740, Anna Ioannovna sat down to dine with Biron. Suddenly she felt sick and fell unconscious. The disease was considered dangerous. Meetings began among senior dignitaries. The issue of succession to the throne was resolved long ago; the empress named her two-month-old child, Ivan Antonovich, as her successor. It remained to be decided who would be regent until he came of age, and Biron was able to gather votes in his favor.

On October 16 (27), the sick empress had a seizure, foreshadowing her imminent death. Anna Ioannovna ordered Osterman and Biron to be called. In their presence, she signed both papers - on the inheritance after her of Ivan Antonovich and on the regency of Biron.

At 9 o'clock in the evening on October 17 (28), 1740, Anna Ioannovna died at the 48th year of her life. Doctors declared the cause of death to be gout combined with urolithiasis. She was buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg.

Peter and Paul Cathedral and the Grand Ducal Tomb.